The Inevitability of Nina

The Inevitability of Nina – Introduction

Dear Nina,

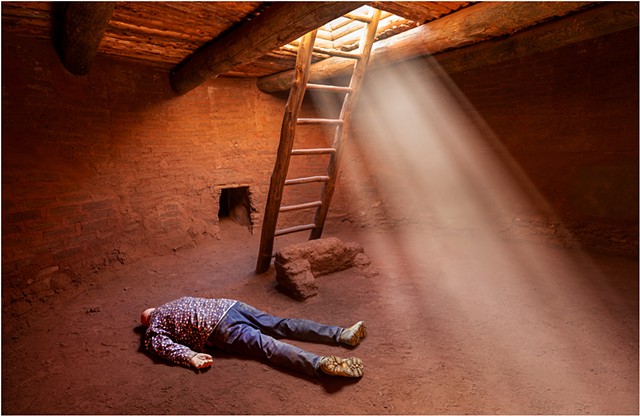

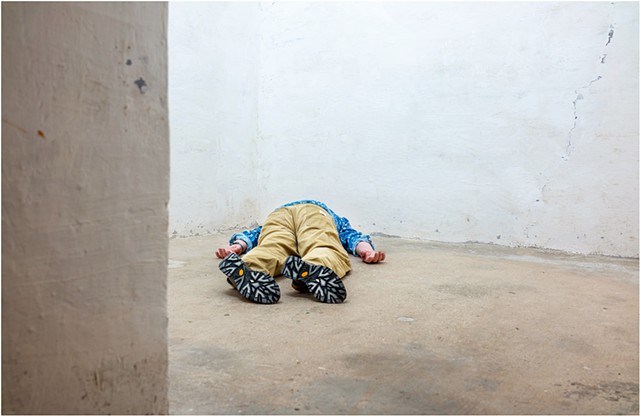

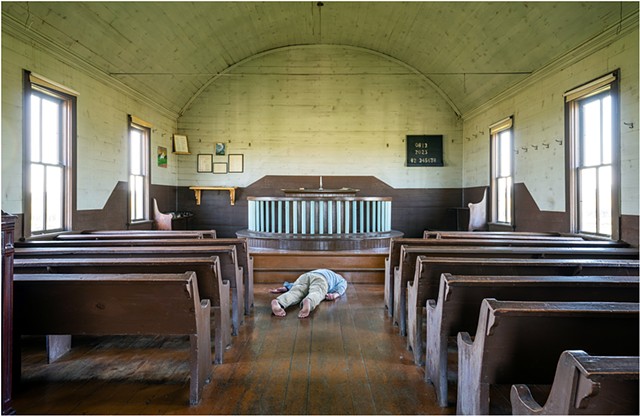

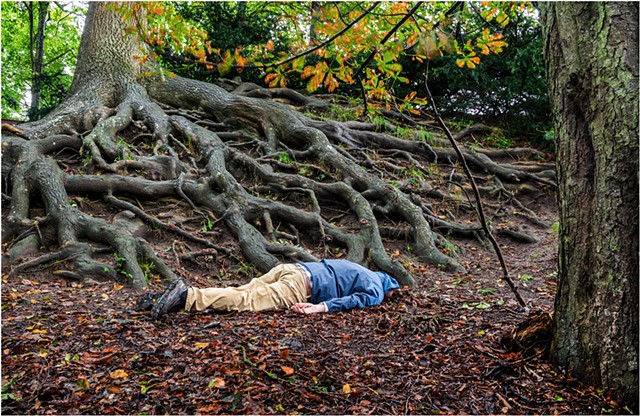

I found you, or perhaps we found each other, at a decisive juncture in the big mystery. I have come to believe it was an inevitable convergence. In Scotland, I had just completed something rich and meaningful, but upon returning to the United States, I was veering off track again. Photography had begun to illuminate the journey, but the light dimmed as I returned to isolation and alcohol – on the road, living in motel rooms and tents. I was back in turbulent waters, heading toward a hellish whirlpool. But miraculously, I found your family photo album, abandoned at an antique mall in Denver. I couldn’t articulate it at the time, but I was drawn to your life as you made the pictures. Your friends were interesting, and they liked you. They reacted positively to your camera. You are reflected in their faces, and I could feel what you felt. Almost instantly, you entered my psyche, and as a result, interconnection emerged as a golden thread in my life and in my photographs. Your timing was good, Nina. The perspective your photographs provided gave me purpose and saved me from self-destruction.

It took ten years for your college memories to infiltrate my photography projects. Your album sat in a box while I concluded my career in mineral exploration and then entered graduate school, where I struggled to find my visual voice because the confidence I had gained as an undergraduate had vanished. I was also in the throes of depression when I entered graduate school, and so the photographs and videos I made reflect that. I tried to see my “self’ in photographs, which, of course, is almost impossible - almost, because there is much to learn from self-scrutiny. Ultimately, however, I concluded that the 'self' does not exist and cannot be defined without an inclusive, universal framework. I was essentially a snapshot photographer, documenting the people and places from my experiences; however, snapshots were not considered a credible art form. I wasn’t sophisticated enough to make the kind of photographs the academy appreciated or to contextualize snapshots meaningfully, so I struggled. Miraculously, I survived, graduated, and, paradoxically, found a home in higher education.

The more often I looked at your pictures and shared them with others, Nina, the more connected I felt to you, your friends, and the places where your pictures were taken. You included a single geographical reference, Jim River, in one of your photographs. An internet search for Jim River, your name, the year (1917), and the State Normal and Industrial School led me to the place where you made the photos, Dickey County, North Dakota. With you and your photographs as guides, a project unlike any I had undertaken began to take shape in my imagination. The principal objective would be to illuminate, at least for us, how everything is connected. Before embarking on my first road trip to North Dakota, the movie What the Bleep Do We Know? was released. The movie’s protagonist is a deaf and mute photographer. Through her lens, quantum theory is explained and illustrated as a unifying concept. I went to see the movie seven nights in a row. It went from obscurity to sensation in a very short time. The first night, I was among a few in the theater. On the seventh night, the line stretched around the building. Subsequent spinoffs corrupted the original’s intentions, but the movie's premise nonetheless strengthened my project objectives.